My love of talking about books comes second only to my love of reading them. It’s a special treat to connect over a mutually experienced work of art, giving the work a second life through remembering and reinterpreting it.

I’d like to share some of the most impactful works I read in 2024 as a reflection exercise and also as a way to connect with other readers. Please comment or message me if you’ve connected personally with any of these works or if you have any recommendations of your own to share from your reading in 2024.

The following list of ten is written in chronological order of when I read it throughout the year, not ordered by any sort of quality-based ranking.

Orientalism by Edward Said

The core of Orientalism: defining from without, not taking what’s said from within as authentic.

I first heard of Orientalism back in 2018 from my Peace Corps partner in crime, Alena Klimas, but remained intimidated by Said’s seminal work until the start of this past year. Said’s overview of the contemporary (18th century onward) relationship between the West (the Occident) and the East (the Orient) is without doubt one of the most impactful works in the field. It is also one of just a few works of such academic rigor and erudition to ascend out of graduate program reading lists and influence the broader culture.

Reading Orientalism was challenging, reflective, elucidating, and inspiring. There’s a powerful tension between the researcher and the researched, the “exotic” and the exoticized, and Said handles these points of tension with sharp wit and a searing tongue.

Said offers a descriptive and wide-ranging depth of knowledge that I will return to when I am ready to be schooled and humbled once more.

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

Demon Copperhead was my first Kingsolver novel. Her first Pulitzer prize winning work is a modern, Appalachian twist on Dickens’s David Copperfield which attentively and tactfully explores poverty, family dynamics, addiction, and social and economic collapse in rural America through the childhood of Damon “Demon” Fields.

Demon, nicknamed after the Demon Copperhead snake due to the red hair he inherited from his absent Melungeon father, is born to a drug-addicted mother living in a trailer in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia. The story is told from Demon’s perspective and Kingsolver nails the sarcastic, self-deprecating tone of a teenage boy growing up in such rough conditions.

The story is rich with memorable characters, thoughtfully constructed relationships, and the heartbreaking reality of the effects of American poverty, all buoyed by the hope that a better life may exist out there after all.

The Alphabet in the Park by Adélia Prado

Prado’s The Alphabet in the Park was the Brazilian poet’s first work published in English and it was well worth the wait. Spanning 15 years worth of poems, Prado attends to the intricacies of human life, especially that which concerns women, with precision and care, merging the physical with the spiritual.

Many of Prado’s poems describe what at first appears mundane and quotidian, only to pull out of these daily occurences a grandiosity that reaches into the divine: she connects simplistic beauty to her interpretation of faith and mysticism.

My favorite moment reading The Alphabet in the Park was when my Brazilian colleague and I read my favorite poem from the collection, Before Names, together during a lunch break at a picnic table outside of our office. In order to understand a line more precisely, she pulled up the original Portuguese version of the poem and explained the nuanced differences between the two versions. It was an incredible experience—thanks again for your insight, Marcela.

The English translation of the poem Before Names can be read here.

Captains of the Sands by Jorge Amado

Another Brazilian read, this 1937 classic was recommended to me by my Aunt Laura as one of her favorite reads from school growing up in Brazil. The novel regales the adventures of a gang of street children called the Captains of the Sands that live together on a beach and work together to survive in an unforgiving world and society that does not accept them.

The children are pushed to steal and scam in order to eat, yet they operate within a strictly enforced code of honor and honesty. Recognizing their vulnerability to outside forces, such as the police and rival gangs, they depend upon one another and form a kind of expansive family unit rooted in values of fairness and reciprocity.

The Captains are led by fifteen year old Pedro Bala, the Bullet, the son of a labor organizer who was killed and marytred during the labor union struggles of the early 20th century. Then there’s the Professor, who reads stolen books “with an anxiety that was almost a fever;” Legless, a boy with a severe limp whose inner pain leads him to mock others ruthlessly; Cat, a Don Juan-type figure with slicked back hair who, at the ripe age of fourteen, becomes a prostitute’s lover; and Big Joao, the largest and strongest of the group who nevertheless has a heart of gold and loves nothing more than listening to the Professor’s adventure stories.

In the year it was published, more than 800 copies were burned in Salvador by Brazilian authorities claiming the work was “dangerous for society.” Indeed, the story includes orphans stealing, fighting, evening molesting each other, and yet I found the novel to be full of whimsy and adventure, including uniquely Brazilian cultural references such as capoeira, candomblé, feijoada, and samba.

Thanks, Aunt Laura, for this rare recommendation!

The Stranger by Albert Camus

The first of what became a series of rereads this fall, I took Camus’s The Stranger with me on a six-day backpacking trip in the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana. I learned my lesson years prior packing heftier novels into the backcountry and so grabbed the slim, 154-page edition of The Stranger as I departed for this year’s annual cousin trip.

I can’t remember when I read The Stranger the first time and my memories of the storyline itself were fuzzy as well, which I think helped lead to a powerful rereading experience as things in the book felt new and fresh.

The story follows Meursault, an apathetic Frenchman living in Algiers during its French occupation in the first half of the 20th century. When his mother dies, Meursault attends the funeral and acts with a stoicism that spectators later point out as unsettling and an indication of his soullessness.

Meursault is a fascinating character in his complete indifference—whether professionally, romantically, or spiritually, he exhibits minimal care about the trajectory his life takes. In this way he is not a very likeable protagonist and yet as I followed his descent and public humiliation, I felt a distant sympathy for his gradual estrangement from society.

Reading the book again I was struck by the subtle power of the novel’s conclusion, when Camus nudges the reader toward a reflection on life’s contradictory smallness and vastness. We will all die one day, so what’s the point? Yet even in the face of impending death there are questions of meaning, of hope, and of belonging.

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

Then a man pours outward, a torrent of him, and yet he is not diminished. And I guess a man’s importance in the world can be measured by the quality and number of his glories. It is a lonely thing but it relates us to the world. It is the mother of all creativeness, and it sets each man separate from all other men.

Kyle of Kyle’s Newsletter and I decided to reread Steinbeck’s magnum opus after Tanner of Ultracrepidarian Hangs read it over the summer. Unlike The Stranger, I still had strong connections with the book and remembered the plot, characters, and central themes quite well.

What stood out most during my second read was the relative depth and flatness of the novel’s characters and how the traits they embody connect with their ability to be agents in their own lives. A few of the novel’s key characters become representations of the book’s central idea, timshel—thou mayest—and therefore take on another layer of importance as the variabilities in their respective personhood drives home Steinbeck’s ideas of individuality and personal choice.

Additionally, Kyle and I spent a lot of time discussing the idea of greatness which is referenced repeatedly in the book. What makes one great? Is it the actualization of one’s potential? The perception of others? The willingness to commit to something lonely and challenging? It is greatness and the grayness around it, more than that of timshel and personal choice, that linger after this most recent read.

The most enjoyable part of rereading the novel was the repeated conversations I got to have with Kyle about it, one of my very best friends and perhaps most dedicated reading partner over the years. I look forward to more such shared reads together in the coming decades.

The Magus by John Fowles

It is what I mean by hazard. There comes a time in each life like a point of fulcrum. At that time you must accept yourself. It is not any more what you will become. It is what you are and always will be. You are too young to know this. You are still becoming. Not being.

Another heavy hitting reread, I first flirted with The Magus while studying in France in the spring of 2016 upon a recommendation from my father who himself had had the book recommended to him by Gary Williams, his English professor and mentor, back in the 1980s at the University of Idaho.

The Magus is a complex, psychological, mythological thriller which takes place on a small Greek island. Nicholas Urfe is a nihilistic orphan (a theme of my reading this year, apparently) recently graduated from Oxford who aspires to be a poet and seeks meaning in his life. He meets Alison Kelly, a young Australian woman, and they begin a passionate affair that ends dramatically when Nicholas departs to teach in Greece.

On the island, Nicholas meets an extremely wealthy Greek recluse who invites him into a labyrinthian series of psychological games involving a pair of beautiful British twins whom Nicholas is trying to suss out while simultaneously falling in love with one of them.

The grandiosity of the novel, Fowles’s vast command of English and Romance languages, its depiction of the paradoxical nature of reality, freedom, and choice, and the mystery borne out of the book’s postmodern, metafictional identity make it one of my all-time favorite books and a work I’ll be sure to return to again.

Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz

He was not accustomed to busying himself with introspection or self-analysis. In this way he was like most people who are rarely alone. His mind did not swing into action until some external force required it: a man or woman or some element of his material life. He had surrendered himself to the busy current of his life, submerging himself totally in it. All he saw of himself was his reflection on the surface of the stream.

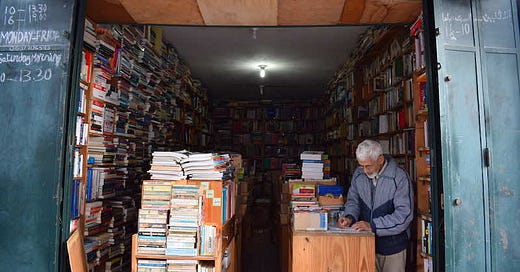

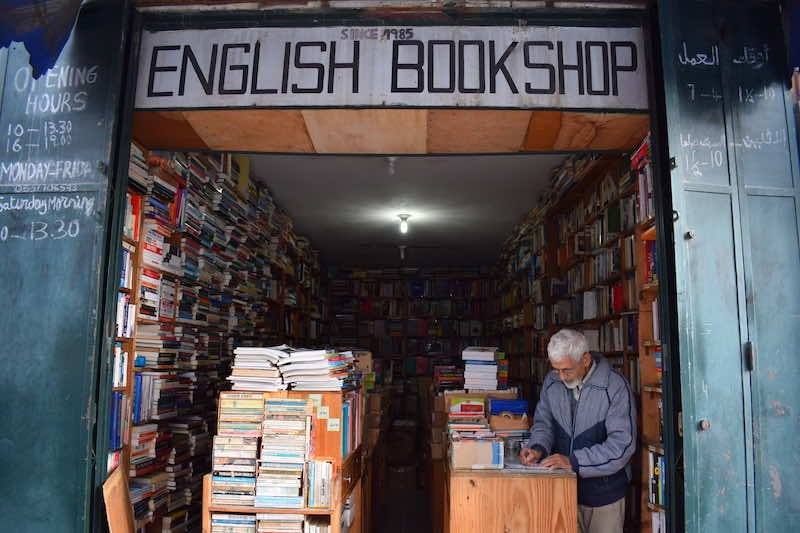

I first heard about Naguib Mahfouz at The English Bookshop, a hole-in-the-wall bookstore in Rabat, Morocco and one of the coolest bookstores I’ve ever been to. There I discovered the second book of Mahfouz’s Cairo Trilogy which piqued my interest and led me to grab Palace Walk from the library when I returned home to Boise.

Palace Walk tells the story of the al-Jawad family in 1917 Cairo, Egypt. The family is run by al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd al-Jawad, an extremely conservative traditionalist at home who runs his family with an iron fist while parading around town as a heavy drinking, bon vivant philanderer in the evenings.

The book offers a view of a traditional, middle class Egyptian family during the British’s control of the country as a formal protectorate. The first half of the novel focuses on family and social dynamics, while the second half shifts its lens toward resistance and rebellion against British rule.

While difficult to stomach at times given my own modern sensibilities, the depiction of honor and the social expectations connected to it, specifically how they inform the way the members of the al-Jawad family perceive themselves and their social standing, provided an insightful look into the psychology of an Arab family at the turn of the 20th century.

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

There were times when he sat watching the boy sleep that he would begin to sob uncontrollably but it wasnt about death. He wasnt sure what it was about but he thought it was about beauty or about goodness. Things that he’d no longer any way to think about at all.

Ah, The Road. McCarthy’s envisioned world of ashe and destruction. A world where survival hinges on the thinnest of margins and no one can be trusted. McCarthy, in an extremely rare interview for the famously reclusive author, told Oprah Winfrey that the inspiration for the novel came when he was visiting El Paso, Texas with his young son and he imagined what the city might look like in the future, with “fires on the hill.”

I undervalued this book the first time I read it. As a McCarthy fan, having heard from so many people that they knew of him only because of The Road, I acted like a snobby hipster and downplayed the book’s significance while pointing to his other works as examples of his mastery of language and storytelling. I have to admit I was wrong: The Road is an incredible work of art that deserves a place in the pantheon of McCarthy’s best.

The feeling of desperation and darkness he paints is pervasive and chilling. A father and son journey across a post-apocalyptic United States that is nearly lifeless and becoming colder as winter arrives. They aim for the sea and trudge dutifully south through ash-covered landscapes full of death and deprivation.

Yet within this world of meagre resources and even less hope, the father imparts upon his son an ethos of benevolence. They must “carry the fire,” he tells his son, providing him purpose within an otherwise bleak, lawless world. They are good—the father repeatedly reminds his son that when the son questions it—and are faced with multiple decisions in which the boy wants to give up some of their minimal resources to help others.

In McCarthy’s oeuvre, The Road stands out as a singular story which offers an epicly dark canvas for his uniquely biblical, sweeping language. I can’t imagine a more heartbreaking and loving ode to a son written by a father.

Passionate Nomad by Jane Fletcher Geniesse

To feel, and think, and learn—learn always: surely that is being alive and young in the real sense. And most people seem to want to stagnate when they reach middle age. I hope I shall not become so, resenting ideas that are not my ideas, and seeing the world with all its changes and growth as a series of congealed formulas.

Passionate Nomad is a biography of Freya Stark, the famed British Arabist and travel writer from the first half of the 20th century. This was another work discovered in connection with The English Bookshop as I flipped through some of Freya’s travel writing there and then came upon her biography at Brused Books in Pullman on Black Friday.

Freya Stark was a woman who would not be denied. Relatively early in life she had a vision of traveling the world and learning eastern languages and she was resolute in her quest for experience and knowledge. As an aspiring language learner and travel writer myself, I was deeply inspired by Freya’s adventures and by Jane Fletcher Geniesse’s beautifully written account of her life.

I was also made aware of the great sacrifices one makes in building a life around travel and language learning. Reading Freya’s life story made me reflect upon my own values and choices and think critically about what must be traded for a chance at a life like hers.

More than anything, however, I recgonized Freya’s great courage and the independence and stubborness required to do what she did. If you want to make something of your life that goes against the norms of the community around you, her life seems to say, it involves risk and sacrifice. At the same time, it offers the enticing chance to enter into a whole new world of experience, learning, and connection.

What to read in 2025? Part of the joy is the process of discovery involved—you never know what will pop up until it does.

Happy reading out there, everyone! And please do share some of your favorite reads of 2024.